What’s up in Swedish children’s literature?

Values, concepts, themes and titles … Bleak humour, rebellious children, gender issues, winter landscapes… Are there any particular themes or motives that might be seen as characteristic of Swedish children’s and young adult literature? A reflection by Malin Nauwerck.

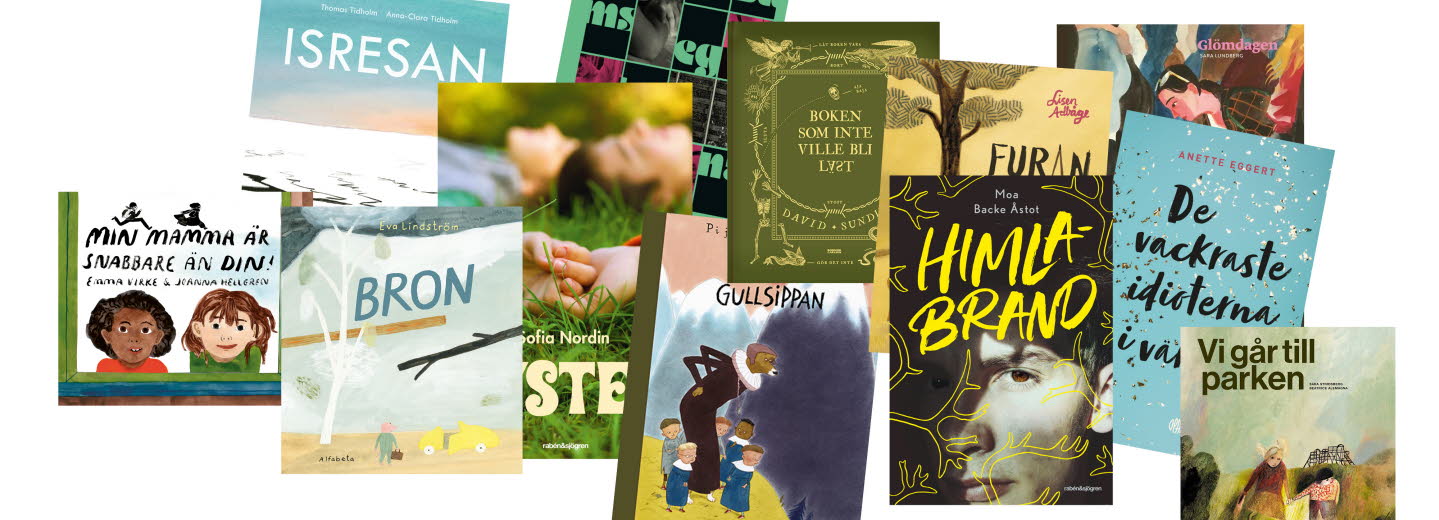

In this article, I take a look at some of the guiding values and ideas that have shaped Swedish children’s literature for a century or more. Against that backdrop, I consider three specific themes that appear prominently in contemporary literature, using a number of excellent recent titles as examples.

First, however, let me say a few words about Swedish as a source language in children’s literature. It is easy to think of Sweden as a small country on the periphery of Europe, but in fact, its position within the global literary system is fairly strong. Swedish itself has been estimated as one of the top sixteen literary languages (thanks in large part to the Nobel Prize). The past fifteen years have seen a big rise in translations of Swedish literature, owing partly to a vast international interest in Swedish crime fiction. Historically speaking, however, the most successful translated genre to come out of Sweden has been children’s and YA literature, which over the past 50 years has accounted for more than half of Sweden’s literary exports.

Guiding values in Swedish literature for young people

In the groundbreaking book The Century of the Child (1900), Swedish intellectual Ellen Key predicted that the twentieth century would be a period of intensified focus and progressive thinking in the areas of children’s rights, child development and child wellbeing. Under Key’s influence, children’s specific abilities and potentials came to be seen as “competences”. Children in Swedish fiction were no longer portrayed as naughty, mean or mischievous. Instead, they became independent, curious or wild. They began to dream, to think, to wonder; to ask questions and explore realms both real and imaginary; to rebel against the prejudices and rules of the adult world.

This way of portraying children in literature is both intertwined with and reliant upon the so-called “child’s perspective”. As it pertains to form and narrative, the child’s perspective typically means that the narrator’s voice is on the child’s level, that emotion and humour are relatable for children, that language and logic are age-appropriate and reflect how children speak, think and feel.

Another important aspect of the child’s perspective is the dynamic interplay in a children’s book between text and illustrations. The gap between words and images is a space that activates the reader and encourages them toward interpretations of their own.

The Swedish author Lennart Hellsing once wrote that children’s fiction and adult fiction are not opposites, but two of many branches on the tree of art. Hellsing’s observation implies that children’s literature does not need to be watered-down or preachy. Works for children may very well be aesthetically advanced; in both text and illustrations, they may embrace the avante-garde.

Finally, Swedish children’s literature hase traditionally been expected to address not just the light but also the dark side of childhood. Swedish children’s books may describe psychologically painful situations; they may arouse feelings of grief or anxiety. Children who are neglected or not seen, adults who do not act like adults, and unsafe environments – even family environments – are all recurring motifs. It is not that children need to be frightened; but (as Astrid Lindgren repeatedly said) children, like adults, do need to be unsettled by art.

The notion of the “competent” child, the use of the child’s perspective, and the conviction that children, no less than adults, need and deserve access to art – all these ideas powerfully influenced Swedish children’s literature during the twentieth century. They remain vital influences today, shaping many of the major themes that can be identified in the children’s literature of recent years. These themes are the subject of annual inventories and analyses made by the Swedish Institute for Children’s Books. Three of them are presented below.

Three major themes in contemporary Swedish fiction for children and young adults

- Ecological sustainability

The environment has traditionally been an important feature of Swedish children’s literature. Recent books have explored the theme of the environment from a wide variety of angles.

In Lisen Adbåge’s unsettling picture book Furan (Pine, 2021), a felled tree haunts a middle-class family who are only trying to build their dream home. As the story grows ever more absurd – the children’s feet start to feel thirsty, a bird nests in the mother’s mouth –the family comes to realise that they are actually transforming into the trees they cut down.

In Isresan (The Ice Journey, 2020), Anna-Clara and Thomas Tidholm tell the story of an imaginary polar expedition. Written as a travel journal in three chapters, the book is an illustrated Arctic adventure story but also includes a list of activities for when you have to live alone in a hut for three years with nothing to do: sit and talk to yourself, dance around with your clothes on inside out, paint your face with charcoal, draw patterns on the walls, sing old songs you learned in school, pretend to be a stranger. Isresan is a story about creative play, but also about recognising – not idealising – boredom and social isolation.

- Social sustainability

Swedish children’s literature in general displays a strong engagement with contemporary developments, conflicts, and societal problems, including those that arise from social divides or how we see one another. Today’s authors and illustrators clearly encourage an inclusive perspective.

A typical example is Pija Lindenbaum’s Vitvivan och Gullsippan (Prim Anemones and Wood Roses, 2021), which deals with social injustice in a playful allegorical setting. Two groups of children have each been assigned different tasks by “the Chief”. The Prim Anemones stand in line, take music lessons, paint, and sail little boats, while the Wood Roses serve, wash up, and haul rocks. The Chief might like injustice, but the children find their own cure for the situation by literally walking in each other’s shoes.

In recent years, the subject of gender equality has also figured consistently in Swedish young adult novels, and several 2021 titles bring added depth and nuance to the discussion. Both Charlotta Lannebo’s Ensamseglarna (Lone Wolves), about a psychologically abusive relationship, and Anette Eggers’ family drama De vackraste idioterna i världen (The Most Beautiful Idiots in the World), are stories about navigating relationships and personal desires in a society where feminism is mainstream. Syster (Sister), by Sofia Nordin, likewise explores domestic violence and power relationships in a nuanced and hopeful way, opening a doorway to less conventional ways of living.

The beautifully written Himlabrand (Polar Fire, 2021), by debut novelist Moa Backe Åstot, is a love story between two young reindeer herders belonging to Sweden’s indigenous Sámi community that breaks with the conventions of the HBTQI coming-of-age novel. Instead of depicting the way out of an insular small town, Himlabrand shows how experiences shared across generations can contribute to progressive change.

- Play and imagination

Play is perhaps the most common element in most children’s literature, and one which is constantly dealt with in new ways. Increasingly, play has also begun to inform the composition and form of books. Some authors have experimented with nonlinear storytelling, or with creating a counterpoint between illustration and text where the two contradict each other, as in Eva Lindström’s Bron (The Bridge, 2020). Play also shapes the narrative in Emma Virke and Joanna Hallgren’s Min mamma är snabbare än din (My Mum Is the Quickest, 2021), which takes the form of a verbal competition between two friends who make up their own story about mums who jump over busses, cycle, run and outswim sharks to get to their children.

Occasionally, the physical object of the book contains elements of play: by being expandable or unfoldable; having interactive flaps, spreads or jackets; or “refusing to be read” by employing graphic strategies such as changing or removing letters from the page, as in David Sundin’s Boken som inte ville bli last (The Book That Did Not Want To Be Read, 2020). In Glömdagen (The Day of Forgetting, 2021), author and illustrator Sara Lundberg presents the reader with two opposing stories: one that takes place in bright, colourful, realistic city setting, and one that undermines it, told in a completely different tone, in sketches on matte paper.

Play as theme and play as form come together in the Gesamtkunstverk or “total work of art” that is Sara Stridsberg’s and Beatrice Alemagna’s lavish collaboration, Vi går till parken (Playgrounds, 2021). Here, the park shares all the potential of literary fiction:

“The park is a forest in the city. It is the land beyond.

In the park, anything can happen. Sometimes so much happens

that the whole world is overturned. Sometimes nothing happens at all.

It doesn’t matter. We just want to go there.”

Malin Nauwerck. Photo: Johan Åhström.

Information about the books in this article

Lisen Adbåge (b. 1982)

Furan (The Pine Tree), Rabén & Sjögren, 2021, picturebook

Rights: Rabén & Sjögren Agency

Thomas Tidholm , Anna-Clara Tidholm

Isresan (The Expedition on Ice), Alfabeta 2020, children’s fiction

Rights: Alfabeta Foreign Righs

Pija Lindenbaum Vitvivan och Gullsippan (Lilybell and Bluevalley), Lilla Piratförlaget, 2021, picture book

Rights: Lilla Piratförlaget Agency

Charlotta Lannebo (b. 1974)

Ensamseglarna (Lone Wolves), Rabén & Sjögren, 2021, YA novel

Rights: Rabén & Sjögren Agency

Anette Eggert (b. 1975)

De vackraste idioterna i världen (The Most Beautiful Idiots in the World)

Opal, 2021, YA novel

Rights: Opal Agency

Sofia Nordin (b. 1974)

Syster (Sister), Rabén & Sjögren, 2022, YA novel

Rights: Koja Agency

Moa Backe Åstot (b. 1998)

Himlabrand (Polar Fire), Rabén & Sjögren, 2021, YA novel

Rights: Rabén & Sjögren Agency

Eva Lindström (b. 1952)

Bron (The Bridge), Alfabeta, 2020, picture book

Alfabeta Foreign Rights

Emma Virke (b. 1974) and Joanna Hallgren, ill. (b.1981)

Min mamma är snabbare än din (My Mum is Faster Than Yours!), Lilla Piratförlaget,

2021, picture book

Rights: Lilla Piratförlaget Foreign Rights

David Sundin (b. 1976) and Alexis Holmqvist, ill. (b. 1980)

Boken som inte ville bli läst (The Book That Did Not Want To Be Read), Bonnier Carlsen, 2020, picture book

Rights: Salomonsson Agency

Sara Lundberg (b. 1971)

Glömdagen (Forgetting Day), Bokförlaget Mirando, 2021, picture book

Rights: Koja Agency

Sara Stridsberg (b. 1972) and Beatrice Alemagna, ill. (b. 1973)

Vi går till parken, Bokförlaget Mirando, 2021, picture book

Rights: Koja Agency

References

Hellsing, Lennart, Tankar om barnlitteraturen, Raben & Sjögren, 1963.

Annual “Book Tasting” reports are available in English translations on the website of the Swedish Institute for Children’s Books. The themes presented in this article are discussed at length in the book tastings from 2018–2021.

Rhedin, Ulla, Bilderbokens hemligheter, Alfabeta, 2004.

Lindgren, Astrid, in Dagens Nyheter, 8 september 1959.

Sweden’s position in the global literary system is explored in:

Nauwerck, Malin, A World of Myths: World Literature and Storytelling in Canongate’s Myths Series, PhD thesis, Litteraturvetenskapliga institutionen, Uppsala, 2018. Available from the author upon request.

It is also described in Swedish in:

Svedjedal, Johan, “Förord [Preface]”, in Svensk litteratur som världslitteratur: En antologi, ed. Johan Svedjedal, Avdelningen för litteratursociologi vid Litteraturvetenskapliga institutionen i Uppsala, 2011.